THIS FEATURE WAS PUBLISHED IN ADB ISSUE #378 – MARCH 2011 || Words // IAIN KELLY PICS // ADB ARCHIVE

The bikes of today were a distant pipedream back in the mid-1970s, when ADB hit the shelves. In the following 30 years, developments have taken us from twin shocks at the back, to a single unit under the seat, along with four-strokes gaining water-cooling, forks growing in size and complexity, frames shedding weight and plastics being used in ever-increasing and varied ways.

Lately, dirt bike evolution has centered on fuelling and electrics. EFI and its associated electronic revolution came to the dirt-scoot fraternity almost 25 years after it had become commonplace in cars, and – as we’re now seeing – ABS, traction control and adjustable suspension appear on dirt bikes, what technologies can we expect will be adapted for our bush bandits in the future?

Are these electronic gizmos to be feared or revered? How will fragile sensors work submerged in a bog or river crossing, or being belted off berms and tabletops? Will the average rider be able – or afford – to service these newfangled bits?

Only time will tell, but for now, here are some of the trinkets which could (realistically) adorn dirt bikes in the next few years.

Fuels

Although MX and SX racers can get away with running almost any race fuel they want (including the new, MA-legal VP Roo100 race juice), people wanting to keep their bikes registered (and on the good side of Johnny Law) have had to rely almost solely on 98 octane premium unleaded. However, there is a new fuel to make your bike go harder and run cleaner.

You might have noticed the press about E85 fuel, or seen the new E85 model Holden Commodore around. This bioethanol flex fuel has been a huge talking point in car circles as people get excited over its power-adding ability, lower tailpipe emissions and the possibility it’ll extend the life of fossil fuels by a few decades.

It isn’t the same as aftermarket race-only (and lead-based) fuels on offer from VP, Sunoco or Elf. The chemical construction of the fuels are different and they’re more closely related to traditional pump fuels, rather than their alcoholic cousins, ethanol and methanol.

Basically, E85 is a blend of regular petrol and ethanol (the “85” refers to the percentage of ethanol to petrol), which has methanol-like properties. For those who’ve spent time around speedways or drag cars, you’ll know that means lots of bang per fuel injection as the alcohol-based ethanol (and methanol) can handle much more timing advance than petroleum.

However, unlike raw methanol, with E85 you don’t get watery eyes and the voracious consumption is quelled – though high-performance motors often take 30% more E85 to the engine compared to standard 98RON premium unleaded.

There are currently roughly 21 million vehicles capable of running the E85 fuel, and their popularity is rising rapidly. Could we see dirt bikes getting in on this action? It is certainly feasible in the future.

Running E85 in an existing dirt bike could be hazardous for reliability due to the fuel’s alcoholic properties destroying rubber fuel lines and the need to re-jet or fine-tune the ECU’s timing settings.

We’re only at the forefront of new fuel technology, but it will make for interesting times ahead.

Launch Control

Launch control could become the hot new trick for MX/SX and cross-country race bikes. Who doesn’t want easily repeatable, cracking fast launches every time? CDI ignition and EFI systems mean factory-fitted launch control is a possibility these days.

An extra output on the ECU, a couple of sensors, a switch and some R&D to set-up perfect launch RPM are really all that stands in the way of holeshot heaven (and plenty of burned exhaust valves). How it works is simple in theory: the ECU cuts fuel and spark to limit engine RPM to a pre-determined value, thereby taking the guesswork out of getting the best mix of wheelspin and grip.

Its use on dirt bikes would have to be managed, as each type of track surface (mud, clay, thick loam, dry and dusty and more) would require a different ECU map tailored for the grip levels, using different peak RPM launch values. This could easily be overcome with a handlebar-mounted switch with several pre-set options the factory can set-up.

With a hand-held ECU interface, like the GYTR PowerTuner or a laptop, owners could potentially set their own launch limits. Car owners with aftermarket ECUs can already do this (provided the ECU has the capability), and in many cases it is as simple as clicking the box in the launch control menu and entering an RPM value for the ECU to use.

Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be fool-proof as the rider would still have to control the clutch and pick the right setting for the conditions. While most bush-bashers don’t need launch control, it could be something offered on factory race models – so long as people understand the strains it places on engines and clutches.

Variable Valves

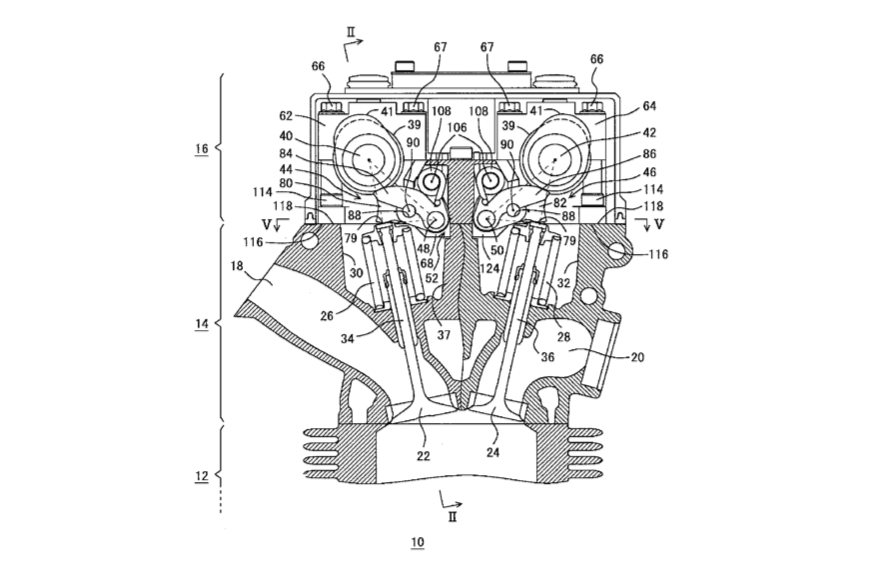

In late 2009, Yamaha patented variable valve adjustment technology (called Variable Cam Timing, or VCT) for four-valve and two-valve heads. Two-strokes already have RPM-sensitive power valve technology, so this is almost the four-stroke dirt bike engine catching up.

The idea behind it is to alter the lift, duration and timing of the valve operation, depending on the RPM point. By allowing the camshaft timing to change, you can enjoy a greater spread of power and torque, improving efficiency, response and power.

Normally, the system senses an increase in RPM and throttle input (ie: you crack the gas) and it increases the opening time of the valves to allow the most amount of air into the combustion chamber possible – thereby replicating fitting a massive race camshaft, without the associated gutless low-end and horrible cold starting.

Most systems operate off oil pressure (like Honda’s VTEC) to operate the solenoids which switch to a second, more aggressive, set of cam lobes, using sensors in the engine (including throttle position, crank angle and cam angle) to safeguard the donk.

This tech isn’t for race bikes, but large adventure bikes and some big-cube trail machines will find it handy for touring and open conditions as it will allow a creamy low-end to build into a screaming top-end (for over-taking manoeuvres, Mr Police Officer).

Direct Injection

Direct injection is likely to be the next “big thing” in dirt bikes. This has been proven by boutique marque Ossa recently debuting a 250 two-stroke trials bike featuring the new style of fuel injection.

With a greater angle for fuel input, as well as more defined control of the combustion, direct injection has given huge gains in fuel efficiency, cylinder temperature, burn rates and power production in passenger cars.

For motors spending most of their time pegged in the top-end – like 250F MX and enduro race bikes, for example – it is a more stable way to provide fuel to a hungry motor and wind more ignition timing into the tune (sharpening throttle response and providing a bigger combustion), too.

With the lack of big-budget development in motorbikes, it is unlikely we’ll see manufacturers racing to drastically change their casting and tooling for engines for direct injection. Instead, it will most likely trickle down from top-end or Factory race bikes to more pedestrian models over coming years.

Carbon Fibre

Carbon fibre and other composite materials haven’t seen as much use in dirt biking yet compared to MotoGP, for a few reasons – the first of which is expense. To make carbon fibre – and we’re talking the good stuff used in actual race cars and bikes, not the fiberglass-packed stuff kids buy to stick on their $2000 Honda Civic – it’s labour intensive.

Aeronautical companies haven’t been helping as they’ve been buying up huge stocks of the stuff. On top of this, if you want to make it strong enough to withstand the big stacks and big jumps dirt bikes endure, then it’ll lose some of its weight advantage as extra layers will need to be added.

A carbon fibre frame is not likely to be something MX, SX or enduro guys will use as they’ll crack from stress too easily – aluminium would be a better choice there, although it is arguable if the weight savings are worth it over a modern alloy frame. Still, for freestyle or trials guys – or others who want a very light bike – a CF frame might be of some use. Joe Gibbs Racing thought so when they unveiled the infamous Toyota-liveried YZ450F concept bike at the ’09 SEMA show.

The reality is, people are more likely to see carbon fibre limited to use as component pieces (handlebars, swing-arms and brakes) than anywhere else, just the same as on cars. It won’t come cheap, though.

Plastic

Light, strong, flexible, modern plastics are used in everything from planes to guns to integral parts of car engines. We already have fuel tanks and shrouds (and subframes on Husabergs) made out of the stuff, so why not a complete plastic dirt bike?

If manufacturers put enough R&D into it, there’s no reason smaller bikes couldn’t be made with a plastic frame. With the weight of the engine, you’d want to limit it to 150cc as the big 300 dingers and 450s would most likely twist the plastic up over time.

Plastic chassis are feasible from a material and cost point of view, though longevity is the million dollar question – would a plastic bike last under an Aussie rider? There’s no question for racing – it just isn’t strong enough, but for trail riding it might be.

Precious Metals

Car manufacturers have been building chassis and suspension arms out of aluminium lately, dropping the tare weight of some seriously large vehicles by hundreds of kilos. It’s taken decades to get to a point they can do this for these highly-stressed parts of the car, and it is still very expensive to do so. Once only the domain of top-line Audis, Jaguars, Lamborghinis and other hypercars, it’s now filtering down to more mundane machinery.

The big benefit to an aluminium frame over other options is it is lighter than alloys (it can be as light as carbon fibre), but withstands cracking under vibration or large shock loads. Unfortunately, it is also softer than carbon fibre, which is bad for handlebars, but good for areas which need to flex very slightly to absorb shock.

Don’t be surprised if you see more aluminium being used in dirt bikes in the next five years, possibly even an all-aluminium chassis on a Factory bike!

Active Suspension

It’s already here. Ducati already have adjustable, active suspension on their quasi-adventure bike, the Multistrada. Their system, imaginatively called Ducati Electronic Suspension (DES) utilises four settings, which you change off the left switchgear.

“Touring” softens the damping and spring rates, sharpens up the ABS and traction control, while “Urban” cuts the power and increases traction control sensitivity, “Enduro” raises the suspension for more clearance and cuts traction control intrusion right down, but keeps power at “Urban” levels, “Sport” gives you all the power the engine will make and a mid-level traction control setting. However, the appeal of the Ducati system is it can be customised, to turn off traction control and ABS, or to set individual compression and rebound characteristics.

BMW have a similar, though not as advanced, system on their big GS 1200 adventure bikes, and as electronic fuel injection spreads across other marques and models, there is no doubt we’ll end up with electronically adjustable suspension as a common feature on big bikes.

Rather than fiddling clickers, there is a lot of appeal for Average Joe riders to have pre-programmed suspension settings available on the fly, much like different throttle maps or tunes for different conditions. The more advanced riders need not fear this, either, as Ducati’s system shows – they can still customise their compression and rebound themselves.

The ability to quickly and easily change suspension maps from “mud” to “sand” to “loam” to “tar” is really just an evolutionary step from today’s “traction maps” on fuel injected bikes. Adjustable suspension programs would most likely work in with the ECU to cut power in situations it isn’t needed.

Obviously, this all comes at a cost and it is that reason we (most likely) haven’t seen these additions on our bikes so far.